Sheila Margaret Evelyn Bhalla, nee Scott, 1933-2021. This is a short history of her long adventurous, compassionate, and scholarly life.

All content copyright (c) Bhallas, represented by Upinder S. Bhalla, 2021. Some family images are shared copyright with the Scotts. Content contributed and arranged by the Bhallas and Divya Rastogi. All audio content is property of the artists.

History

Mummy was born in Victoria, Canada, in 1933. Her parents were James Cosme Walter Scott and ‘Molly’ Scott, in full Mary Helen Mabel Scott, nee Bressey.

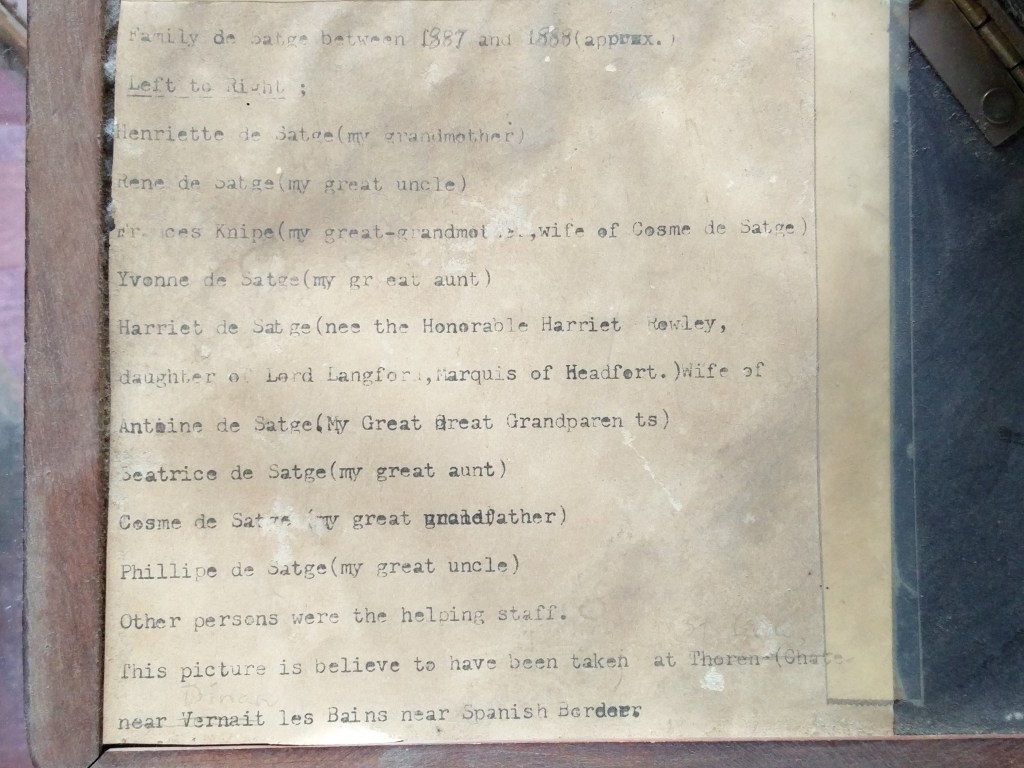

The location of the family picture is probably Château de Thorrent, Lous Clots, 66360 Sahorre, France. This fits the location near Vernait les Bains. It seems to be a quiet, private place, even Google does not reveal any photographs. There is another Château de Thorens, near Geneva, which is very pretty. Mummy and I made a virtual tour of the castle and she quite approved. She told me a story of how Pop (her father) had managed to travel there during the closing days of the War and had wandered around the château, looking at portraits of ancestors.

Mummy tells about looking after the goats and ducks as a small child. One duck would lay its eggs in the water, and they had to fish them out. They lived in a house that her father had made, a log cabin, during the depression. Then the war came. He would connect up the radio listening for the call-up. Mummy was sent to her aunt’s place (Auntie Maggie?) in Victoria.

Among the other stories from her growing years is how she got access to the library of the house where she was staying, and there was a section which they didn’t expect little girls to read. But she read very well. So she would take the books and go hide in the kennel of the ferocious family dog, where no-one would imagine she could be. Another version of the story, or maybe a different adventure, was of her sneaking off to read books in a drainage pipe under a road. She got stuck, and would never have been found. Fortunately she managed to slither out of it.

She picked up her father’s skepticism about non-science. When she was sent to a religious school as a child, she came back one day full of scorn because the teachers were trying to tell them about the holy ghost. “They believe in ghosts!” she said to her father, who was thrilled.

Her mother used to sing Que Sera Sera to Mummy. She loved the song, and when she stayed with us I played it and she sang along. Her father criticised the song because it sounded superstitious, but she loved it anyway.

Mummy tells many stories of their dog, possibly from after the war. This dog loved to jump. He jumped into the airfield, and used to chase the airplanes taking off. He jumped over the fence into the dog pound, to be with his friends, then jumped out again. The staff at the pound got to know him. He was dognapped and taken to Toronto and sold to a new owner. But he escaped and made it all the way back to Ottawa. They were able to trace the new ‘owner’ by the dog tag, and this led to the dognappers.

Around her school years she trained as a long-distance swimmer. She credited that for her life-long fitness. She relates about going for a swim, and her hair freezing in the cold when she returned. She also served as a life-guard and relates how she had to kick free and subdue a particularly large drowner before he was limp enough to let her tow him to safety.

She had a lovely alto singing voice and was part of a school choir that toured the region and also the US. Since she was the shortest she got put in front of the group.

She loved to hear “Jesu joy of man’s desire” by Bach. It was one of the choral pieces.

I would play it for her when she was in our home in her last year, and again when I visited her in Pondy. It brought back memories, and she sang along.

She told Ravi of a time when she and some friends went hiking on Christmas, and the last bus to return did not turn up. They were freezing. They found shelter in a church and there was a working phone with which they managed to call for help. In those days, a working phone meant a mechanical switchboard somewhere, and not everyone was connected.

Presumably soon after this she went to work in a factory, really to help to organize the union. She was spotted right away.

One of her jobs was in a cardboard factory. At that time women did not do muscle labour, but she was just the right height for a pressing machine which had a food pedal that required strength. I think that was also when she managed to break her ribs, took medical leave, and went hiking to the highest peak in the district.

She remembers being academically at the top in math. But for some reason her father (despite being progressive in many ways) didn’t really wish her to go to college and thought she should go to a finishing school instead. She saved money from various summer jobs and invested them in stocks for the first and last time of her life. This gave her sufficient money to go to college. She did very well, and her father was proud of her.

When Pete Seeger was being persecuted in the US during the McCarthy era, he went around playing very small venues and student places. I think Mummy may have been at U Ottawa, when he came by, and played in a very small and nearly empty hall, to a few very cold people. Mummy among them.

I don’t know when to place her stories about getting Algerian students out of France during the Algerian war. This bitter war lasted from 1954 to 1962 and the French police were rounding up all Algerians. Presumably Mummy’s adventure was in the earlier half of this period, since later she went to London to do Masters in Economics at LSE where she met Daddy. They had rescued a tall Algerian who had insisted on staying in Paris till he was awarded his PhD. The group had a cover story that they were going around helping to repair buildings. Their rescuee climbed up to get a good look, where he was very visible and endangered them all. The group had many colorful characters, such as the Jesuit worker-priest who knew two words of English: Getup and shutup. Another character got drunk and went to a street, guarded by non-humorous men with guns, and jumped like a frog down the street. Eventually the group smuggled their Algerian student across the Belgian border in a van full of vegetables, and then sauntered across in the guise of young tourists. They completed the transfer through the back of a pub, which had a back door down to the water’s edge. Mummy had the assignment to pick dance songs on the jukebox and cause a distraction by the dancing. She recounts how they looked out across the bay as the sun set, and could only see one vessel that could have taken the Algerian student away – a tanker a long way out. Her story was that nobody could see how to get from the shore to the tanker, so there must have been a submarine. [Shireen probably has this story in its entirety on recordings]

The love of my life

In her last years, Mummy was asked about sitting back and enjoying her work, garden and all. She said to Ravi, “But I don’t have the love of my life…”

Below is ‘Too old to dream’, by Vera Lynn. The original song talks about ‘your kiss will live in my heart’ but Mummy always remembered it as ‘a song will live in my heart’.

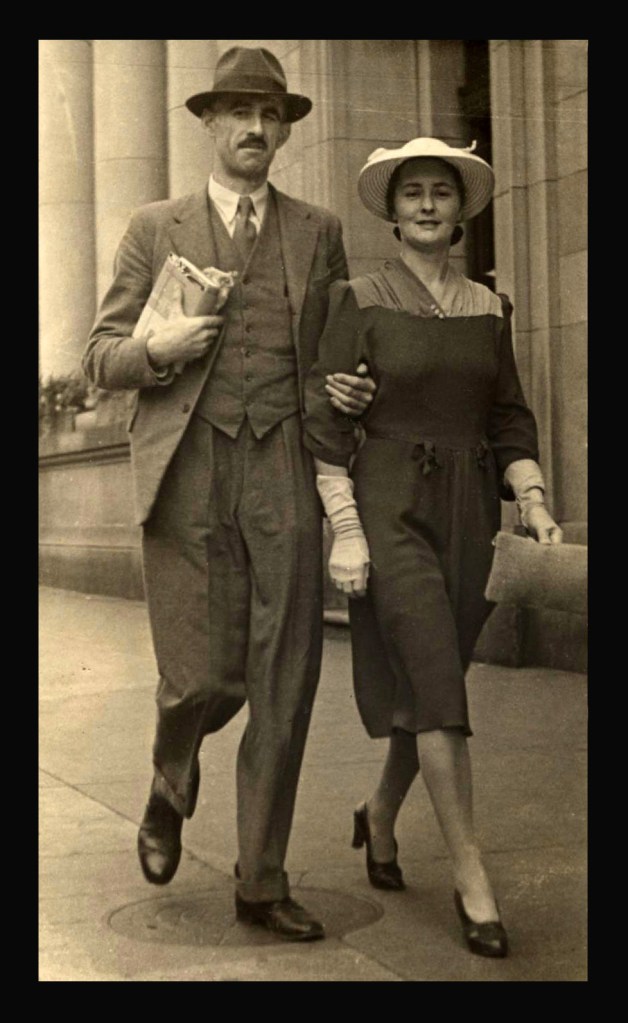

They met as active members of the Left/Communist parties, when Daddy was running for student union president. Mummy relates taking him to speak at the Canadian group to canvas for votes, and I guess things went on from there. To her last days she remembered the free student tickets and going to concerts with Daddy. When I mentioned, in possibly my last call with her, how Shireen had gone to the Globe Theatre to see Romeo and Juliet, Mummy recalled the student tickets that they used to provide for free, and how one could pull them off a peg. She and Daddy went to see the same ballet (Swan lake?) twice, because one set of tickets was in English and another in French. Daddy couldn’t tell that they were to the same show, but they went anyway. I guess the ballet wasn’t the main purpose after all.

Mummy went on a tour with Daddy around this time, hitchhiking through Scotland. It must have been one of the happiest times of her life, since she told all of us the story many times. They were piked up by a truck driver who had an amazing voice. He regaled them with many songs, including “The Scottish Soldier”. In later tellings of her story the Scottish Driver became a famous singer. Here is Andy Stewart’s rendition.

I heard this version many times on a 45 vinyl recording that Mummy and Daddy must have bought around then, and put it into our small family collection of music.

What I didn’t get to hear was Daddy’s rendition of “Three blind mice,” which she attempted to teach him during the same trip. He was quite tone deaf and could not get the tune. A source of joy and laughter.

Mummy heard Paul Robeson in concert, and his ‘mighty voice’ was henceforth the standard by which she measured all others.

Daddy had his PhD from London School of Economics and Mummy had her Master’s viva when she was very close to term with me. She relates how the examining committee looked at her girth and decided that this was going to be a very short interview. Then, when I was born, she had arranged with Daddy to be picked up from the hospital at a certain time. Knowing Mummy, she was out in the cold and rain of the London kerbside well ahead of time. Sure enough, Daddy himself was late – he had stopped off at a pub to celebrate my birth with his buddies. Mummy at a kerbside with a baby waiting for Daddy. Seems to have been a theme all their lives together.

She came to India, to Moga in heartland Punjab, with a fifteen-day old infant. Aunties told me about people rushing to the house to see the “Mem” (memsahib) who had appeared. They got their first jobs at the University of Jaipur, where they formed life-long friendships with the Narulas and others. Sharan was born there.

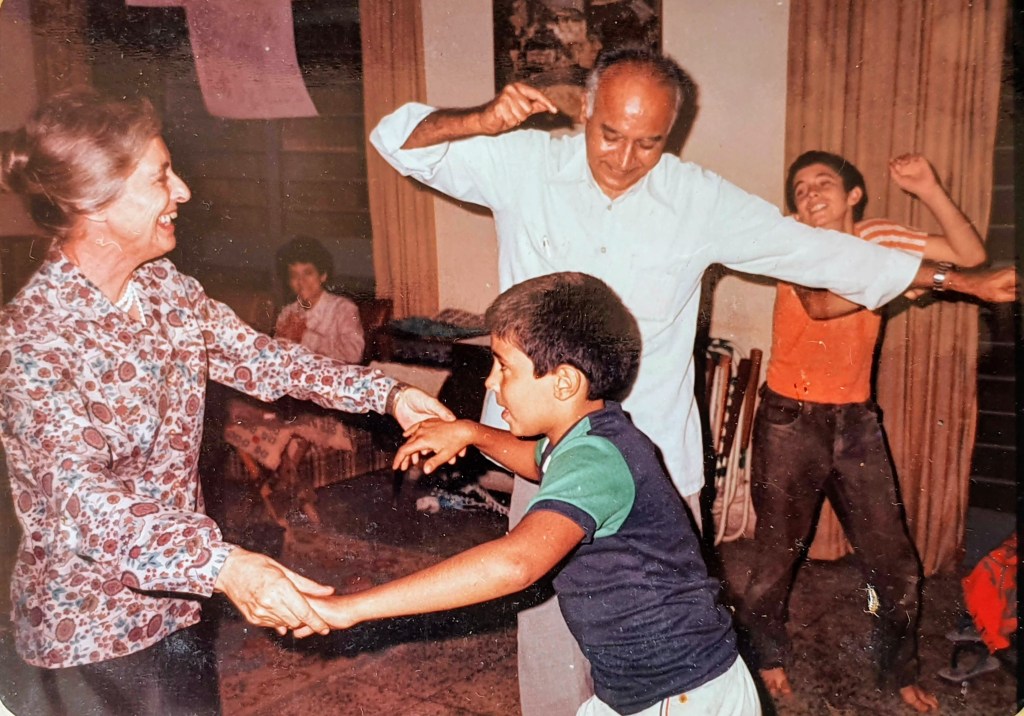

Mummy was given some money by her parents to return in case she didn’t like India. But she and Daddy used up all the money on beer! She and Daddy used to dance to this, when we played it on our record player at 102 JNU. For a while.

After a couple of years in Jaipur they went to the University of Ottawa for another two years. Ravi was born there. I have a few memories of Mummy from Canada. I had been jumping on a sofa with Sharan, and her foot got stuck, and she howled. Mummy rushed in, logically assumed that I had done it, and smacked me. So I joined the chorus. Sharan came to my defense. I remember Mummy enlisting me (or permitting me) to help her with spray-painting some furniture. I think my panels ran paint. Years later, Daddy complained to me that Mummy always had the thermostat turned way high. Maybe that is why they came back to India.

They worked in Panjab University Chandigarh for some years from 1969. We stayed in a little row house, E1-28, which had at various times our nuclear family (with the addition of Yogi), Daddy’s parents, assorted aunts and cousins, and a dog or two.

Mummy kept this incredible assortment going in as much harmony as one could manage. Here is a story of those days, which stuck in my mind because I didn’t quite understand what was going on. I had run across the word “legend” in a book, and I went to Mummy to ask her what it meant. She told me to go and talk to Baiji, my father’s father. He had been a school-teacher. Somewhat dubious about it (why would an old Indian school teacher know something Mummy didn’t?), I did go. And so I got to spend a few minutes with my grandfather, who spent much of his time alone. It took me years to realize what Mummy was doing with this little invisible act of kindness.

In 1975 we left Chandigarh for Delhi, where they were among the founding faculty members in the new Jawaharlal Nehru University. Mummy was at the Centre for Economic Studies and Planning and Daddy at the Centre for the Study of Regional Development. We were in house number 102, which soon became a hub for evening get togethers for scholarship, political debate and beer.

Mummy retired around 1998, and they moved to a new house in National Media Centre in Gurgaon. Mummy designed the house herself, to fit the particular shape of the corner plot, and the young architect admired its profile. She planned several spare rooms, with the idea that it would be a place for multiple generations of children and grandchildren to come and visit. And indeed we did, though we were now starting to scatter around the world.

By then I had moved to Bangalore. I’d come to visit periodically when work took me to Delhi. Once, around 2000, I had brought little Shireen along because Gitu had her hands more than full with Boots. I left her with Mummy for the day. I returned to Media Centre after a long day of committees. I looked out from the car and I saw Shireen in Mummy’s arms, waiting by the side of the road, because she missed her Daddy. Echoes of waiting for another Daddy, a generation ago.

And, of course, Mummy’s new home had a garden! More on this decades-long project below.

Incomplete

The garden

Mummy was the organized, on-time anchor for the family. She would prepare for flights days before, and as she aged she would be up and ready at midnight for a midday flight. At first glimpse her sudden going left so much incomplete and it saddens me to think of her garden, and her book. But I’m wrong. Her garden was complete in every moment she worked on it.

Earlier her projects were grander, from the rocks shaped like the prow of a ship which she packed into her airline checking baggage to ship from Bangalore to Delhi. This formed the keystone of two sweeping arcs of stone.

There was the planning of terraces and hanging trees just so over the new house in 40 Media Centre. Later, it was the turn of seasons from planting to spring, to perennials trimmed back and double watering to keep the garden going through the parched months till the exuberance of the rains. In all the flowering splendour and somewhat over-stepped lawn she would sit with Daddy and a beer, later alone, collecting her thoughts. I could come any day and be regaled with plans for rocks, and colour combinations with the roses, and the battle with the bandicoots.

Later still, it was trudging up the stairs with a pot despite my pleading to think about her stents, and giving the sun-birds a sprinkle shower. All complete in themselves, in the doing. I grieved when she left her garden at 40 Media Centre, without, as I suggested, a last walk around it. Maybe she had already said her goodbyes. I wasn’t even there when she said her goodbyes to the garden in 102 JNU. But I see now that her garden was not incomplete, because the completeness was in the doing. I’m still sorry for the abandoned garden. Once she had thought to write a book about how to garden for Delhi’s extremes. Never started, maybe incomplete only in my imagination. What’s incomplete is only notes to self, to call Mummy in the evening.

A garden is a lovesome thing, God wot! Rose plot Fringed pool Fern'd grot- The veriest school Of peace, and yet the fool Contends that God is not - Not God! in gardens! when the eve is cool? Nay, but I have a sign; 'Tis very sure God walks in mine -- Thomas Brown.

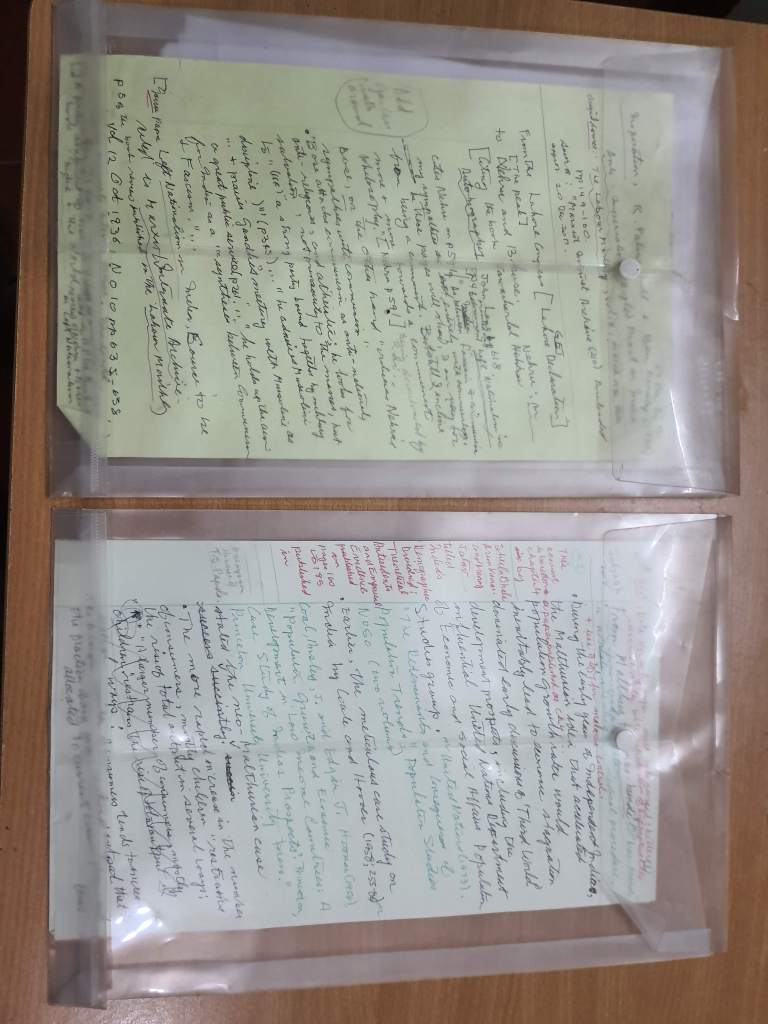

A history of Indian labour and trade unions since independence

Of all her unfinished work, this grieves me the most. When small strokes were whittling away at Daddy’s neurons, but he could still work, it was really Mummy who helped to get it over the threshold, with his co-author. Mummy read and rewrote the passages which Daddy could not manage, and she saw that it came out though I don’t know if it even acknowledges that she should have been an author. But Mummy’s great work, which was years in the making, lost years while she first helped Daddy with his work, and then in his last years on the farm. She treasured her work, I can only guess at its sweep. She took the manuscript – stacks of pages in transparent folders, cartons of references – from her office in Delhi to her home, then to my home, then to the farm in Pondicherry. It was always the first thing she packed. It sprawled in untidy stacks in 40 Media Centre. It took up residence under the desk in Bangalore. In Pondicherry it overflowed over a bookshelf. For the year of coronavirus she said she could not write without her computer. But I think that by then the abrasion of time ahead taken from her all but the treasuring of her work of love. She did not write again, in her remaining months.

I’ve glanced at a few pages. Meticulous cross-referencing and somewhere, in her mind, was the grand structure of the book. There is no-one to co-author for her, as she had done for Daddy.

I’ve heard from some of her students and colleagues, and they have indicated an interest in looking at her notes to see if the book can be completed, after all. It would be a tribute both to her own scholarship, and to the esteem of generations of students.

Enjoying life

Mummy was stuck at home for many months during the first Covid wave. This was very hard on her. But she broke loose to take part in a protest with the Kisan Sabha (Farmers Union) in front of Parliament, in 2020. She went and protested with hundreds of people, standing for hours along with them. She remained committed to worker’s and farmer’s rights to the very end.

Trump served as a particular inspiration to Mummy. She was quite addicted to CNN, which had its regular news shows and commentaries that were deeply indebted to Trump for so much material. It was her entertainment every evening for the months she stayed with me, from the campaign to the long-drawn out election to the boggling lunacy that followed it. She had her favourite news analysts. She loved to sit with her beer and watch the commentary. She rather lost interest in the news after Trump finally exited and gave way to a much less entertaining Biden.

I had planned this web page to be a project I would build up with her, using her reminisces as material as we went along. In my last visit with her in Pondicherry, on 21 August 2021, I sat with her one evening with some old photographs. Ravi had carefully removed them from their frames and brought over from Delhi so that they could be scanned and so that she could see them. Here is the edited recording.

The frogs and cicadas were singing in the background, and the dogs and cat came and visited. A small glimpse of the evenings she enjoyed on the farm, and of her reminiscing about people she loved.

2022

Weekend call.

Hello Mummy It is time for our weekend call I've scraped small doings from the week Fragments of my life that might connect to your receding horizons. I went to the lake where we walked in the setting sun. The baby storks have all flown But the pelicans still sail to the islands. We celebrated Diwali And set out two candles, one for you and one for Edie They burnt long, through a thunderstorm that you would have loved to watch, and the small flames stayed lit as night came on. Two little girls - You remember Zahra, she sang old songs with her band One evening, and you sat out in the lawn to listen. - little girls came to light their sparklers on the candles we set out to remember you. And I welcomed them, because forever in your life You were the steady flame that gave light to children. I watched for a while, then stepped back into my life. In the morning your flame was gone But I remember and the children grow on. Upinder S. Bhalla Nov 2021

Ever green

Ever green Watching over growing things hovering like the sunbirds in the spray of your hose like clouds of mist over arrays of potted plants in nurseries But not like sentimental angels over the cribs of little children. No, like grit, and fire and joy in life and owning your own deeds and someday, giving on. Ever green. Upinder S. Bhalla Nov 2021